If you wander through the Phoneix park today you may arrive at a small roundabout, located in the center of the park, containing a tall Corinthian column with a proud golden phoenix bird atop. You might idle why one of the largest city parks in Europe, many miles from Greece, should be dedicated to a mythology bird. The question then might rapidly disappear as you try to cross the busy road but I suspect you would be surprised that the reason has to do with water, specifically a clear spring pool that used to exist in the area. If you’ve read the first article in this series, which mentions how Dublin got it’s name, then you may guess where this is going. In the local Gaelic tongue “clear water” would be “fionn uisce” which, anglicized, became “Phoenix”. The old name however can still be found in the official Gaelic name; Páirc an Fhionnuisce

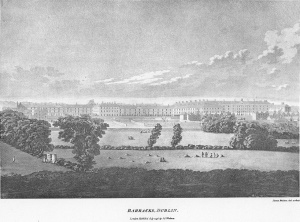

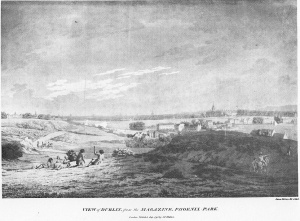

The park, as currently constituted, is a subset of the lands which Strongbow, the Earl of Pembroke,  granted the Knights Templar in 1174. Kilmainham, south of the river, would also have been included – indeed the Knights Templar built their abbey on what is today the Royal Hospital, Kilmainham – the building right of center in Maltons print. The Office of Public Works however claims 1662 as the Parks birth year when the Duke of Ormond created the Phoenix deer park. We will leave the OPW to their foibles.

granted the Knights Templar in 1174. Kilmainham, south of the river, would also have been included – indeed the Knights Templar built their abbey on what is today the Royal Hospital, Kilmainham – the building right of center in Maltons print. The Office of Public Works however claims 1662 as the Parks birth year when the Duke of Ormond created the Phoenix deer park. We will leave the OPW to their foibles.

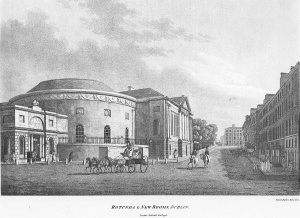

In 1611 the land was granted to Sir Edward Fisher who had constructed Phoenix House just north of the river. Fisher sold the land and house back to the crown in 1618 and the building would be used by the viceroys until 1665. In 1735 the building was removed and replaced by The Magazine Fort; the major distribution point for arms and munitions to other barracks in the Dublin area. After independence the fort would carry on in it’s designated role for the newly formed Irish Army but would be suffer a major indignity in December 1939 when the fort was raided by the IRA who stole 1,084,000 rounds of ammunition. Today the fort is closed and abandoned.

View of Dublin from the Magazine, Phoenix Park. August, 2013

View of Dublin from the Magazine, Phoenix Park. August, 2013